![]()

CE Quizzes Home |Feline Ocular Diseases Quiz

The two most common feline ocular diseases: what every technician should know

WINNIPEG, MB − ORLANDO, FL − Feline herpes virus (FHV-1) and anterior uveitis are the two most common feline ocular diseases a general practitioner will see. FHV-1 has many presentations and associated complications while anterior uveitis is a complicated disease with many causes, explained Kerry L. Ketring, DVM, DACVO and Tammie Flood, RVT, VOTS, presenting at the North American Veterinary Conference. Knowing more about these common diseases and the drug reactions associated with their treatment will allow technicians to more effectively communicate with clients.

Feline herpes virus

The same feline herpes virus (FHV-1) that causes rhinotracheitis in cats causes four ocular syndromes: ophthalmia neonatorum in the newborn, bilateral keratoconjunctivitis in young cats associated with active rhinotracheitis, acute conjunctivitis, and unilateral or bilateral ulcerative keratoconjunctivitis without associated systemic disease in young and adult cats. Dr. Ketring said that he believes that all cats may have feline herpes virus in their system, and that stress may cause a recrudescence or relapse of a latent infection.

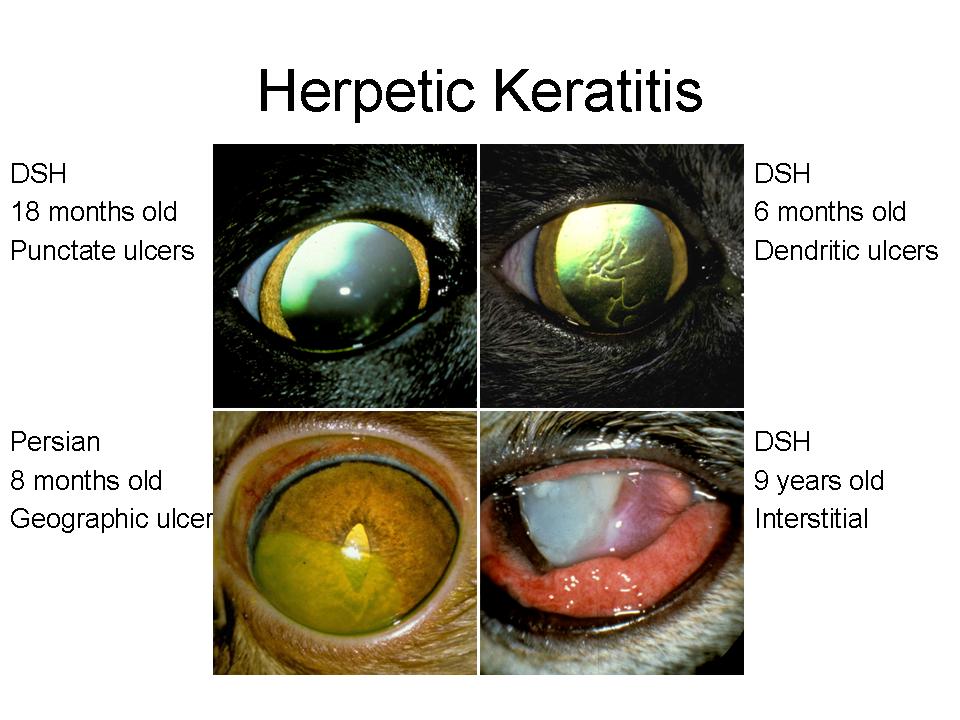

The four clinical presentations of ulcerative keratitis seen in the adult cat include punctate, dendritic, geographic, and stromal ulcers (Fig. 1); all four forms may be unilateral or bilateral and only the last form is a threat to vision. The cat may be presented with severe blepharospasms, conjunctival hyperemia, or serous to seromucoid ocular discharge. Early cases may have only the pain and severe conjunctival involvement without corneal ulcers. Cases may also present with no subjective signs of pain, little to no conjunctival hyperemia, yet multiple linear and punctate superficial ulcers and a history of increased tearing.

Figure 1

In all three forms of the disease, tear production may be decreased. Secondary anterior uveitis may be present especially with the stromal form of the disease.

Diagnostic tests, not readily available, are lengthy and expensive while other tests have a high incidence of false negative results. Of the different tests, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique has proven to be the most reliable. Dr. Ketring added that due to the high incidence of asymptomatic carriers, a positive does not prove that the virus is the cause of the clinical signs.

He said that a response to therapy and clinical signs may be the best diagnostic test. If the condition worsens with topical corticosteroids, a herpes infection is frequently indicated. With specific antiviral drugs, response to therapy is usually rapid; within 48 hours, hyperemia and blepharospasms will reduce.

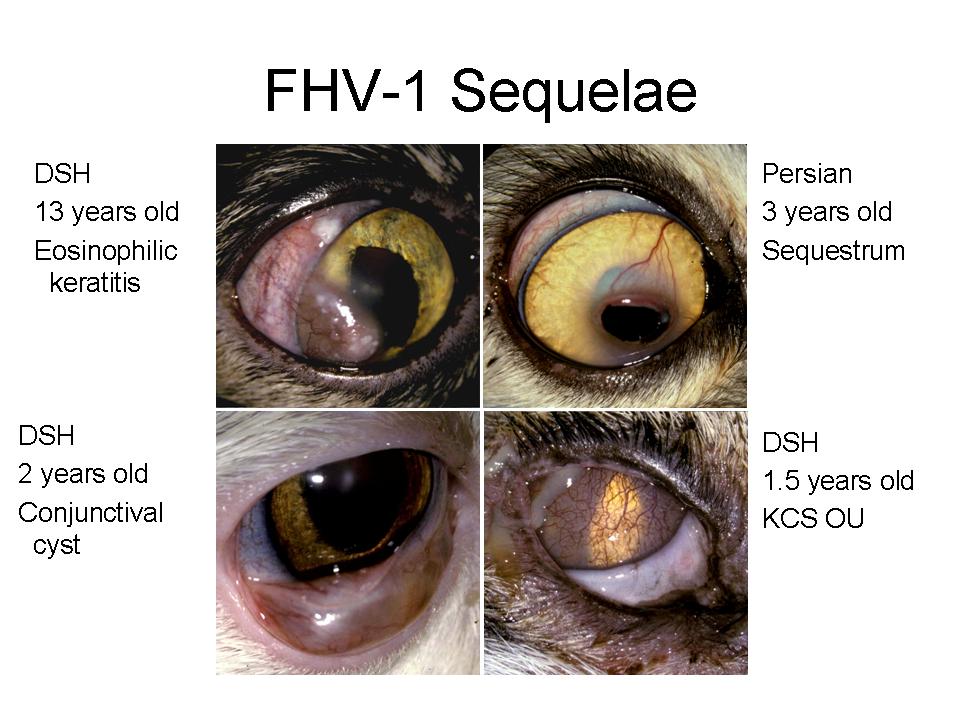

Sequelae to feline herpes virus include eosinophilic keratitis, corneal sequestrum, symblepharon, KCS, conjunctival cysts, scarring of the nasolacrimal puncta and duct, and Mycoplasma corneal ulceration (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

Five topical medications are now available with specific antiviral activity: adenosine arabinoside (Vira A®), trifluridine (Viroptic®), trifluridine generic, and idoxuridine (IDU) solution and ointment generic. Topical interferon alpha 2b is available from formulating pharmacies. The newest topical drug is a nucleoside analogue cidofovir, formulated as a .5% solution from an intravenous preparation, but Dr. Ketring said it is expensive.

Unfortunately, he added, all antiviral drugs can cause local irritation manifested by increased blepharospasms and hyperemia of the conjunctiva and lid margins. Due to the frequent incidence of adverse reactions to other drugs, i.e. atropine and antibiotics, minimal drugs should be used. In cases of severe drug reactions, the topical antiviral must be altered.

There are three oral medications currently used to treat FHV-1: interferon, L-lysine, and famciclovir (Famvir®). All have shown to be effective, not only for active cases but to prevent recurrence. Dr. Ketring said that he uses L-lysine in all cases as an effective, inexpensive, and safe drug to prevent recurrence. However, recurrence rate is high and therefore the client should be advised. Cases of recurrent attacks, or severe stromal involvement should be evaluated for FeLV and FIV.

Dr. Ketring stressed the importance of educating the client that FHV-1 is seldom totally eliminated from the affected cat. The virus becomes quiescent, only to relapse under stress. The aim of long term therapy is to reduce exacerbations.

Anterior uveitis

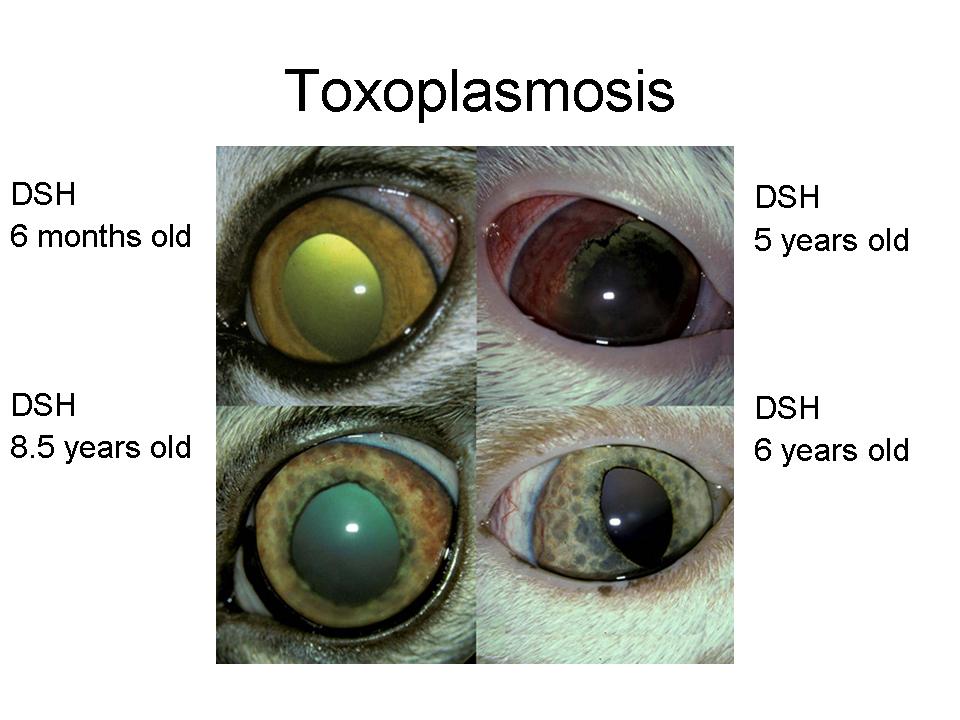

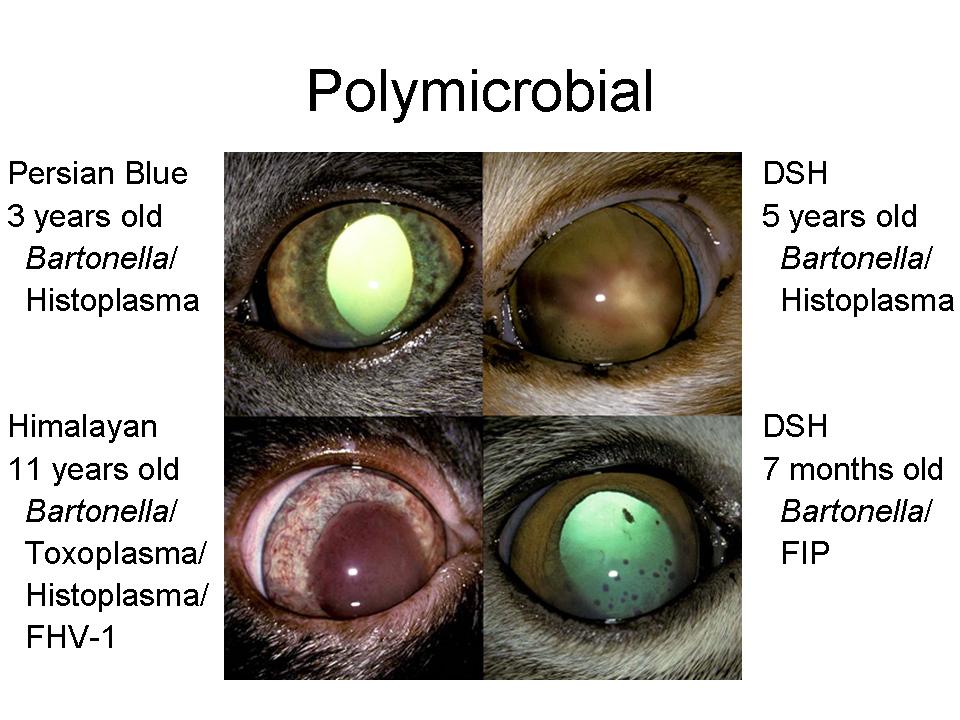

Anterior uveitis or iridocyclitis is inflammation of the iris and ciliary body. Trauma, lens-induced and metabolic diseases i.e. systemic hypertension and blood dyscrasias, may be possible etiologies. The incidence of anterior uveitis in the cat is second only to keratitis and/or conjunctivitis cases in its frequency in both general and specialty practices. Dr. Ketring said that determining the etiology of anterior uveitis is often the most frustrating part of the entire clinical syndrome. It is generally accepted that both unilateral and bilateral involvement are most often associated with one or more systemic infections or neoplastic conditions (Table 1; Fig. 3). Polymicrobial cases are not uncommon (Fig. 4), and these require specific drugs for each microbe identified.

Figure 3

It is important to establish a primary etiology for feline uveitis since this may indicate specific therapy, affect long-term prognosis, identify a contagious disease among other cats in the household, and may establish the occurrence of a disease with public health significance. The list of possible etiologies may be shortened by determining the age of the cat, associated clinical or systemic signs, the exact appearance of the anterior uveitis, and any other ocular involvement. Following an initial examination, thoracic, skull, and abdominal radiographs may provide additional information. Usually, without an etiology determined, the veterinarian will submit a CBC, chemistry profile, protein electrophoresis, and serologies for every disease known to cause anterior uveitis. Ophthalmologists may go a step further and perform a paracentesis of the aqueous or vitreous fluid. Cytology, cultures, titres, and PCR performed on ocular fluid may yield a definitive etiology.

Table 1: Etiology of feline anterior uveitis – endogenous/infectious

Bacteria: Viruses: Feline Infectious Peritonitis Virus (FIPV) |

Parasitic:

|

Figure 4

The diagnostic work-up is often expensive and frustrating for both the client and veterinarian and the results may prove to be very subjective or difficult to evaluate. A definitive etiology is determined ante-mortem in less than 50% of the cases. Dr. Ketring explained that in severe cases where the animal’s life is in jeopardy, or where the eye does not respond to therapy and is blind and/or painful, enucleation and histopathology may be a valuable aid in determining a definitive etiology. The type of inflammatory response, appearance of neoplastic cells, or in some cases, such as mycotic infections, the identification of organisms may lead to a specific etiology. He added that one commonly held assumption is that many cases of lymphoplasmacytic anterior uveitis are caused by prior infections with toxoplasmosis. This hypothesis has been based on the known incidence of toxoplasmosis in cats, the frequent presence of low titres to the organism, the difficulty in identifying microorganisms in the ocular tissue, and the documented lymphoplasmacytic cellular response to Toxoplasma infection. It is well documented that Bartonella can also be associated with a lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory reaction in various tissues.

Treatment

Oral and/or topical antibiotics or antifungals are indicated only if a specific etiology

can be determined. Oral corticosteroids may be of benefit if not contraindicated by

associated diseases. Topical corticosteroids and NSAIDs are indicated in all cases.

Atropine, which is indicated initially in most cases, reduces the pain associated with

ciliary spasms and dilates the pupil to prevent posterior synechia.